By Surendra Bhatia

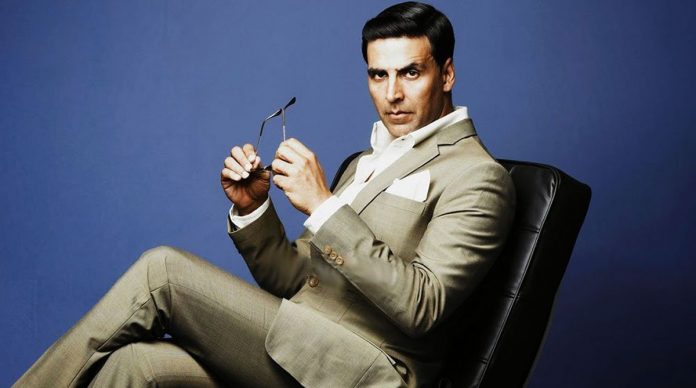

There’s something that Akshay Kumar is doing, which is so right that it’s a wonder that nobody else is following in his footsteps. While other big stars have had massive troughs and crests in the past many years, Akshay’s career graph has been as steady as a snail travelling along a tree branch. If he slips up occasionally, no one really notices, but most times, he’s moving along till, with time, comes the realisation that he’s managed to come a long way.

Somewhere back in his career, Akshay seems to have had an epiphany. Like all top stars, he was in a desperate race to hurl blockbusters at audiences, with each film structured around the stuff stars and filmmakers believed ‘the public wanted’. This involved churning the formula to try and give it newness while ensuring that only tried-and-tested content was dished out. So, songs, dances, romance, fights, comedy track, emotions were thrown into the melting pot and then stir-fried with heavy dose of masala and delivered to the public. However, people’s taste had become eclectic. Sometimes, they bit and the film did become a super-hit but more often than not, audiences reflected that movie critics’ favourite headline of ‘old wine in new bottle’ was not uncalled for.

Akshay suffered as did Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan, with potential blockbusters being stalled because audiences did not care and would not pay up for overheated and stale masala-infused dishes. A single flop doesn’t put the brakes on an A-lister’s career but when career choices show diminishing returns, a little introspection is not inappropriate.

One other example showed out like a lighthouse in the darkness threatening to descend on star careers. Aamir Khan prospered with almost every film. He did not see the troughs that pulled others down and sucked in their films. Majestically, almost every film Aamir made (Lagaan, Taare Zameen Par, etc.) was lapped up by not just audiences but critics too. And – this is the bit that introspection should have thrown up for all stars but only Akshay seemed to have caught the message – the films Aamir made had very little to do with the formula that ruled movies of other stars. Aamir picked up an interesting story, created an engrossing narrative around it and did not wander away, importantly, from the central theme into item songs and unnecessary stunt fights, and he delivered it to audiences as a ‘special’ film. And it worked every time. Taare Zameen Par should never have been screened in multiplexes for more than two-three shows a day across screens… it did not have the ‘entertainment’ that propels films into audiences’ good books. But, somehow, instead of giving audiences what they wanted, Aamir started offering them what he wanted them to have, and he met with success after success, irrespective of the scale and production values of his films. Sometime in the future, film historians would realise that Aamir had actually offered Bollywood a path back to the Golden 1950s when filmmakers like Raj Kapoor, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy, Guru Dutt, Vijay Anand made story-centric films, and audiences simply lapped them up. Now, Aamir was doing the same – making films of stories he liked, and doing it with a degree of sensitivity, and had found almost instantaneous support from audiences. His films did not often have the content that marks blockbuster but yet, Aamir’s films rarely missed bull’s eye.

Akshay was sharp. He picked up Aamir’s game plan and decided to give up competing with Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan for blockbusters and instead planned to race against the one and only Aamir. Basically, Akshay shifted his career from the crowded orbit of formulaic filmmaking to the rather rarefied story-centric orbit which was sparsely populated. It seemed a strange turn for the star who had survived for years by turning out Khiladi films, who danced like school children did PT, and fought like a mix of Tarzan and Bruce Lee, and who was not known to be much of an actor. But, having decided to shift gears and get into the slower lane, Akshay put all his might into it.

Somewhere during the time when he was churning out films like Joker and Khiladi 786, he signed an unusual subject about a gang of conmen – Special 26 – which did well at the box-office for precisely the reason that it wasn’t the run-of-the-mill kind. Then came films like Airlift, Singh Is Bliing and Housefull 3… and Airlift, story without romance and about a battle but with minimum fights, brought him the maximum accolades. The film was successful in every which way but, more importantly for Akshay, it was based on a real-life incident which provided him the template for his future choices.

Even though it can be said that, at this point, Akshay looked closely at Aamir’s footsteps and decided to follow them, there’s an essential difference between the two paths. Aamir steadfastly stuck to listening to numerous stories, whittling down the choice to one or two, worked meticulously for months with writers and directors to fine-tune the narrative, and move ahead with one, only after he was thoroughly convinced that it was as good as it could get. This meant that (a) he had to work on it for months before it got cooked enough to shoot, and (b) he could have, maybe, just one release a year or sometimes two in three years.

Akshay did not have the time and probably the patience to go through Aamir’s tedious motions. Or maybe, he just had a lot of faith in his God – which had once made him sign a film just looking at the proposed movie’s poster even though the story was not ready or thought of. So, he made the essential changes to Aamir’s methods and created his own path. Instead of slogging over one story for months, like Aamir, he decided to focus on story-worthy headlines of real-life events. Aamir created authenticity by tweaking the narrative; Akshay decided to pick authenticity from headlines. Once it was decided that a particular newspaper headline could make for a good film, Akshay left the tedious task of building it into a narrative to writers and directors. If they were convinced and he was reasonably satisfied with the outcome, the movie project was on.

Aamir put his eggs in one basket a year; Akshay decided to spread his over three-four baskets a year. However, like Aamir, Akshay too decided to eschew top heroines for these film projects, making do with fresher faces which cost next-to-nothing.

In the two years (2016 and 2017) that Aamir released Dangal and Secret Superstar, Akshay gave audiences five of these small-budget sensible, story-centric films – Airlift, Housefull 3, Rustom, Jolly LLB 2, Naam Shabana, and Toilet Ek Prem Katha. After that, he threw in 2.0, a commercial venture for which, he is reported to have commented, he spent more time and effort than was worth it. Rather surprisingly, all his small films brought Akshay widespread accolades and most were unbridled success stories. None of his films was half as big a hit as Dangal but, collectively, Akshay’s five films brought in as much money into the industry as Aamir’s two. They were operating at different levels in the same orbit but Akshay’s success was no less than the good fortune enjoyed by Aamir who probably garnered greater acclaim but Akshay made up with the commercials.

The streak that Akshay has now hit is, perhaps, the most lucrative of his career. Even when he makes a film about a space journey, littered with technical details, it still works. Mission Mangal has become one of his big hits and will soon become his biggest so far. So many of his recent films are the kind that never got made earlier in Bollywood – whether it is the one about a man innovating a sanitary pad for his wife or the mission to build a toilet. On paper, both – Toilet Ek Prem Katha and Pad Man – were disasters in the making; Akshay managed to convert them into hits – Akshay and audiences, that is. Headline-inspired hits are unique to this actor who was once known as khiladi, for various reasons.

If Aamir does it with such finesse and Akshay slightly ham-handedly, why aren’t the rest of the stars also making films where the story is the actual hero? It should seem obvious to them that this path yields good results.

Well, it is not that none of them is trying. Shah Rukh Khan made When Harry Met Sejal and Zero, which he thought was different, and Shahid Kapoor made Udta Punjab, which was uniquely dark and different. So, the problem is not that they are not trying; it is the fact that they aren’t getting it right. Frankly, besides the idea that they want to tap into audiences that Aamir and Akshay are catering to, the other stars know nothing. Their sensitivities are geared differently, more commercial and more hero-like. If they were presented with stories and scripts like Pad Man and Taare Zameen Par, they would have been reluctant to commit to them for lack of faith. How the hell does a star sign on for a film about sanitary pads? It doesn’t make sense to them. Shahid’s vision is too dark, though Kabir Singh worked superbly at the box-office, to opt for middle-of-the-road common-man films of the kind Akshay is doing. Shah Rukh has thrown up his hands, for the time being, unable to fathom this new genie that Akshay and Aamir are nurturing.

Fortunately, Aamir and Akshay have opened up new vistas in Bollywood where just about any story can work, provided it is well made and packed with sensible content. They have proved that audiences are quite accepting of new ideas, new concepts and new kind of stories. Most filmmakers think of audiences as birds in a cage brought up on a fixed diet, which reject anything new offered. But audiences are now being seen as free birds, which would as happily peck at a Tiger Zinda Hai as they would take a bite of Mission Mangal. They are not the ones in a cage, filmmakers are. And the ones that invest in films had better learn this fast or else they, too, would have to take a sabbatical from films, like Shah Rukh Khan.