By Surendra Bhatia

Where’s The Money?

There’s a trough and there’s a crest and linking the two is a wave. In oceans, these waves are innumerable, extremely swift and short. In real life, the distance between the two can be hours, days, weeks, years, decades or evenions. Bollywood goes through such cycles too. And, over the last few years, a new kind of ebb in the measure of cinema screens seems to have given way to a bounce. This is odd, an unusual upward movement in the wave, tracing number of cinema screens in the country which had been headed downward into a trough since some years. Screens in cinemas across India built up slowly over the years and hit the high of 10,015 in 2012. Then, assaulted by unrealistic escalation in real estate prices, alternate revenue models, dipping quality of Indian films and stagnant box-office collections, some cinemas started drawing the curtains, pulling down shutters, and abandoning the film industry. Closure of cinemas became like a low-grade epidemic. Screens in India dipped to 8,100 in 2015, indicating that as many as 1,915 screens disappeared into oblivion in just three years. In a country starved of cinemas, with vast tracts of each state devoid of the entertainment that a film screen provides, and an echo for more theatres resounding from so many regions, India was actually witnessing the exact reverse: a steep fall in screens instead of a steady rise. At the speed cinemas were closing down, it was estimated that another couple of thousand screens would fade out in the next few years.

But a trough gives birth to a crest, going by the movement of waves. The tide for cinemas in India turned in 2016. The increase in cinema screens wasn’t much but, at least, the fall was arrested and signs of a bounce became visible. From the trough of 2015, 384 screens got added in 2016. The next year, the bounce became a little more visible with another 288 screens lighting up in cinemas. In 2018, the revival was established with another addition to nation-wide screens, this time 218. The up ward movement can be seen and measured, however slow it may be. It has still not crossed the apogee of 2012 (10,015 screens) but it is clear that the trough seen in 2015, with 8,100 screens, is behind us, and the crest is definitely forming and will peak sometime in the future, hopefully.

There’s something odd about the exhibition trade in India, which is difficult to comprehend. There’s no doubt that Indians love watching films and more than a couple of billion tickets get sold in cinemas, the second highest in the world. Yet, cinemas make their profits not as much from box-office sales as from food counters! We have the capacity to absorb another 10,000 cinemas but lack the will and foresight to build them. At a stage when all trades connected to the film industry should be up and sprinting, we tend to crawl, slowly, tediously and with much wasted effort.

There are problems but are they insurmountable? One major issue in India is the low admission rates as India is perceived to be a poor country, or rather a rich country with lots of poor people. According to a 2015 report, sales of tickets in cinema halls in India was 2.1 billion in year 2015, and revenues were $2.1 billion; on the other hand, China saw sale of 2.2 billion tickets the same year and its film industry revenue was pegged at $11 billion. The difference in ticket sales in the two countries is not much but the Chinese film industry’s revenue is five times more than India’s! The difference, of course, lies in pricing of admission tickets.

The general single-screen cinema perception is that if ticket rates are in creased, revenues would drop; no one dares to raise ticket rates, especially in single-screen cinemas because Indian audiences are very price-sensitive and may prefer to stay away from cinemas rather than pay an extra ten rupees. Caught between the hope that a five-rupee increase in rates could make running cinemas more viable and the fear that business would collapse, cinema owners wrestle with the dilemma, they just don’t have the guts or intellect to resolve.

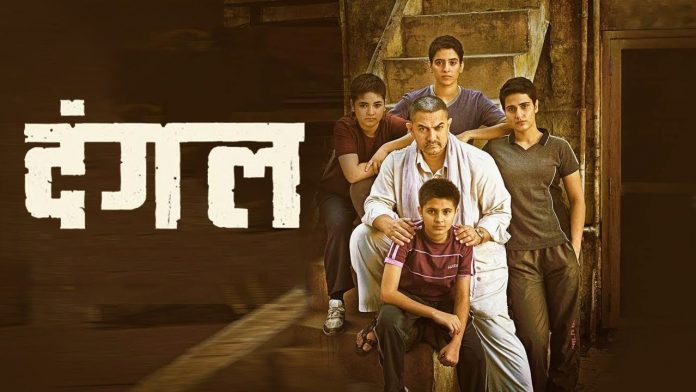

There is a fallacy in both perceptions, that needs to be exposed. One, increase in admission rates does not keep audiences away. The obvious example is that of multiplexes that are generating a lot more revenue for the film industry than single-screen cinemas. People have no compunctions about buying tickets priced at about Rs. 450 each when they perceive, they are getting value for money; a ten-rupee increase in single-screen cinemas will neither lead to riots nor will people abandon the habit of watching films. But for each there is a caveat. Audiences need to perceive value in the entertainment they are being offered. When the film is good, like Dangal or Uri – The Surgical Strike, audiences do not hesitate to put up their money at the box-office window; but if the fare offered is disappointing, even a Rs. 50 spend on a ticket is unattractive and unacceptable.

The quality of films offered by Bollywood plays an important role in convincing audiences to buy tickets. Bollywood has a success percentage of less than 20%. In terms of purchase of tickets at cinemas, 80% of Bollywood films fail the paisa vasool test; these are films on which no one, except the ones who first checked them out on opening days, spends any money, neither Rs. 450 nor Rs. 50. Yet, on the other hand, films starring A-list actors, especially the two Khans still at the top, invariably witness cinema owners jacking up admission prices in the opening weekend to recover the investment faster. There’s hardly any resistance from audiences to this increase when the film is Dangal; when it’s Thugs Of Hindostan, crowds vanish from the box-office window, irrespective of whether the rates are increased or decreased. The issue is always about the film: is it paisa vasool? If it is, ticket rates matter a lot less; if it is not, ticket prices don’t matter at all because people aren’t lining up to buy in any case. If Bollywood delivers better films, cinemas will prosper; unfortunately, the below-average quality of films affects the exhibition trade adversely, both, in its current revenue potential and its future growth plans.

If quality of films is a matter of concern, then the quality of cinemas is yet another material issue. Whenever single-screen cinemas have undertaken renovations and have spruced up their premises and upgraded their audio-visual systems, they have been able to increase the admission price and faced no resistance from audiences. But, it is difficult for a single-screen cinema to increase admission rates while the state of the cinema is deteriorating. It boils down again, probably, to the concept of paisa vasool. Audiences are not idiots. If air-conditioning is switched off for half the film, if seats are torn and uncomfortable, and washrooms are filthy, there certainly will be resentment among audiences when rates are increased. It might be prudent for cinemas to first offer the facilities and then claim redress.

There’s another small fact that provides the underpinnings to how much be nefit good-quality films bring to the industry. Last year’s calculations show that just 13 hit films brought in over Rs. 2,000 crore to the industry in box-office collections, while 237 others, mildly successful, commission earners and flops, collectively got not even anywhere close to Rs. 1,000 crore! This is astonishing. Cinemas screening Bollywood films survived and thrived only because of these 13 films; the other 237 films were just fillers that took up time and maybe helped pay cinema workers’ salaries but threw up no profits.

Now, if you look at it another way: if Bollywood would supply to cinemas 30 hit films a year instead of 13, the industry would boom and, of course, cinemas would be making money hand over fist and growing by leaps and bounds. The quality of Bollywood films just simply has to improve for the allied trades to grow. It’s the only factor holding everything and everyone back. If more hit films reach cinemas, it would act as a panacea: increased revenues would provide exhibitors the incentive to expand their portfolio, spread out into the countryside (which is grossly underserved in entertainment hubs) and bring back to the film industry twofold or three- fold revenues. Even facilities in existing cinemas would improve substantially if the crowds came in more often, and cinemas started running to capacity. It’s not rocket science.

On their own, cinemas will grow at their own leisurely pace, running to full houses for about 15 out of 52 weekends, and struggling to pay the air-conditioning bills for 35-odd weeks. Cinemas need the stability of a continuous stream of film audiences wanting to watch films, which they haven’t had as yet. As and when they do, India will be as big a market as China, if not bigger.

Films & Politics

You just can’t keep a good idea down. It is well-known that successful film stars start off with a huge advantage when they turn to politics and stand for elections. Even a faded one like Urmila Matondkar, who was done with substantive roles more than a decade back and hasn’t since been seen much on the big screen, is considered popular enough to be put up against a heavyweight from the rival political party. Whet her they are successful in politics or not, film celebrities are certainly adept at winning elections. We have too many of such examples and need cite none.

Since politics is all about winning elections, politicians have apparently taken note of the ease with which even politically incompetent stars (like Govinda) make it to the Lok Sabha. And they have decided, it seems, to emulate them, to the degree that is possible for them. Narendra Modi (not himself but as a character played by an actor) made an appearance in Uri – The Surgical Stri ke. This was followed up by a full-length film on him and his life struggles to ‘serve the country’, and the release was timed to coincide with general elections this year. How ever, controversy and the Election Commission have managed to keep it from releasing. Meanwhile, a film on Mamata Baner jee’s struggles to ‘serve the nation’ from age seven has also been cleared by the CBFC and is awaiting release. Here too, the character of Mamata is played by an actor.

Have politicians started thinking that biopics can win them elections? It does seem so. Well, in that case, a new revenue stream can open up for reputed but currently out-of-work filmmakers. They just have to put together proposals for biopics of politicians about two years before elections are due, with a promise that the film would be ready in time for release before elections. Finance, for one, would never be a problem. Certainly, there would be a lot of takers for the idea, filmmakers and politicians.

There’s another related issue that needs to be taken note of: the Election Commission has banned the release of the Narendra Modi biopic, accepting the opposition’s argument that the film would unduly influence the electorate. The same fate might await the Mamata Banerjee film. Is it slightly ridiculous? Modi and Mamata are on TV 24×7, addressing rallies, giving interviews, being discussed by studio panels with live videos streamed in the background; every statement they make is avidly dissected on prime time news, and news papers and magazines carry large pictures of them… so, how, in the devil’s name, can a feature film, seen in cinemas by the paying crowds, ‘unduly influence’ the electorate?

Perhaps, not much should be said about the ridiculousness of the EC’s order, not while elections are going on; so more about this after the elections, when the films would, in any case, cease to matter, that is, if they even matter at all before elections.