By Surendra Bhatia

Content Triumphs Over Star Power

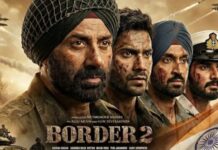

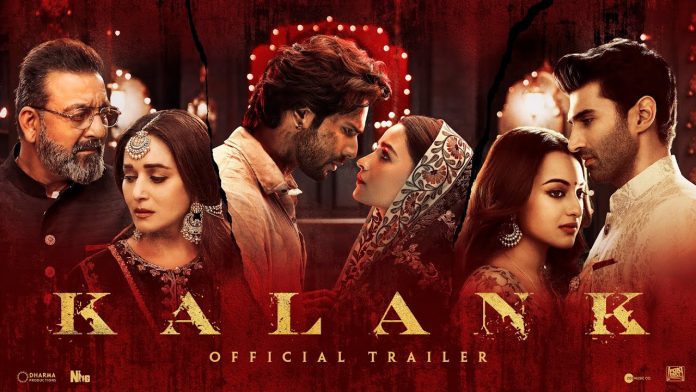

Kalank opened on 17th April with good reviews, hit music and great expectations. The film looked a million bucks with lavish sets, Binod Pradhan’s awesome cinematography and a cast packed with performers. But the high expectations proved to be like some of Bombay’s roads: firm on surface and hollow inside; Kalank slipped and crashed through to a pit from where there’s no recovery. Perhaps, the film deserved better but there’s no arguing with the public verdict.

On its own, the fact that Kalank flopped means little. Films come with their own destiny, and the industry has learnt to live with whatever is thrown at it. However, as a cog in a possible pattern, the non-success of Kalank might give birth to a larger fear: are too many big-budget films failing to hit the bull’s eye at the box-office?

The unnerving truth of 2018 was that each of the big Khans registered a flop in the same year, which hadn’t happened ever in the last 15-20-odd years. Aamir Khan’s Thugs Of Hindostan, Salman’s Race 3 and Shah Rukh’s Zero were the biggest disappointments of last year. Though it doesn’t fall in the Khan category, Kalank, too, seems an extension of the same pattern where a highly-awaited, big-budget film, loaded with stars, ends up running to empty houses after the opening weekend. Within the industry, it has led to an awakening of sorts. It is finally being accepted, with great reluctance, perhaps, that the film’s cast doesn’t any more seduce audiences if the content doesn’t provide a quality back-up. And, for a film to score at the box-office, it needs to be entertaining, irrespective of whether its star cast is of eminence or not.

It’s obviously not a new thought. It’s been around probably from as far back as the end of the first decade of filmmaking. The overwhelming nature of stardom that A-listers possess sometimes obscures the obvious, though the box-office never fails to teach the lesson on a regular basis. Stardom and especially superstardom descends on cinema halls and on fans with an aura of infallibility, with the assumption that the film starring the A-list actor can’t but be a mega blockbuster. And sometimes, this superstardom does work its own wonder. Decades back, Rajesh Khanna had a run of almost 25 super-hit films at the beginning of the ’70s of the previous century. It was a given: any film starring Rajesh Khanna had to celebrate a silver jubilee, at the very least. However, once this golden period came to an end, Rajesh Khanna had to struggle for hits like any other mortal. And that hasn’t changed for any of the superstars that have followed. All of them had hits but interspersed with occasional flops…

However, it has become a little more obvious now, possibly because 2018 saw big stars delivering flops, and a series of small films charming audiences at the box-office disproportionately to the value of their star cast. The fate of a film is now more closely tied in with its merits, irrespective of its star cast. This is not to say that stars or A-listers are irrelevant to a film’s fate. If an A-lister’s film is superbly entertaining and comes with great quality, like Dangal, for instance, the star is able to push its revenue into the stratosphere; Dangal, with a lesser star, would have been a hit but not on the scale that Aamir’s presence took it. But even Aamir, in a film lacking merits, can’t do much except ensure that the first couple of days register decent collections.

Superstars today can take the audience for granted at their own peril. Audiences, faced with multiple choices of entertainment – courtesy the Internet and smart phones – are no longer at the mercy of the cinema hall to transport them into another, more benign world. Years back, Bollywood could boast of captive audiences, but not any longer. Easy accessibility has freed the Indian public from the film industry’s clutches. Now, people will troop to cinemas out of choice, not boredom and for lack of anything better to do.

Bollywood is fast learning that stars are great to pump up audiences and raise their expectations but alongside comes the risk of disappointing them more easily. The primary focus of every filmmaker needs to be on content; stars, like artful packaging, can attract eyeballs but it is ultimately what’s inside the package that matters. It is no longer about big or small film, mega star or non-entity, reputed director or newcomer; it is, as it always was, about entertainment and the idea of paisa vasool. Oft said, always understood and rarely heeded by Bollywood is an old axiom: Content is king.

Typhoon Strikes, Bollywood Hides Under Bed…

A safe prediction and the one already anticipated by Bollywood: Avengers: Endgame will be India’s biggest hit of the year, till now and possibly all through to December. Bollywood has cleared the cinemas for the Hollywood franchise movie, not just for one weekend but two, offering no notable release as competition to the one that is expected to have a humungous opening and a scorching sprint to Rs. 300 crore or even Rs. 400 crore at the Indian box-office. Avengers: Endgame is the ultimate Bollywood nightmare: a rival filmmaker’s mega hit.

Indians had been kept insulated from foreign films to a great extent, far more than any other people. Hollywood managed to swamp countries and audiences across the world and sweep them into its embrace, even the Chinese, but Indians remained immune to its charms. Why Indians didn’t care for Hollywood films, except for an occasional one with nudity or awe-inspiring visuals of disasters, would make a good subject for a doctorate. But they just didn’t. However, that started changing just before the turn of the century. Hollywood broke the language barrier by dubbing its films in local languages, and releasing in a larger number of cinemas. Indians, prodded by the explosion of access to worldwide entertainment via Internet and smart phones, have become more accepting of Hollywood films.

A number of Hollywood films have scaled the Rs. 100 crore ladder in India. The biggest till now has been Avengers: Infinity War (with collections of Rs. 225 crore) followed by Jungle Book 2 (Rs. 187 crore), Fast And Furious 7 (Rs. 95 crore), Avatar (Rs. 90 crore), Jurassic World (Rs. 90 crore), Jurassic World II (Rs. 85 crore), Fast & Furious 8 (Rs. 85 crore), Mission: Impossible 5 (Rs. 80 crore). The latest Avengers: Endgame is poised to beat all these to become the highest-grossing Hollywood film in India… it would not be surprising if it gets very close to Rs. 400 crore and becomes one of the highest grossing films in India.

It is to be expected that Hollywood films, by and large, will do much better business in India in the coming years. Part of the reason is that Indian audiences now have greater exposure to the world and are more aware about what’s going on in the Western world. Another small factor might also be the general mediocre quality of Indian films, which don’t compare favourably with Hollywood movies. Third, and more important one is that Hollywood dubs its films in many Indian languages and spends a lot more on promotions. It may still be some way off but it would not be surprising if five years from now, about 15 Hollywood films notch up Rs. 100-crore-plus collections in India annually.

Bollywood should consider itself blessed that films from other nations haven’t started making inroads into the Indian box-office as yet. Till now, it’s only English films from Hollywood and England that have shown traction with our audiences. Hardly any films from China, Mexico, Spain, Russia, Japan or even English-speaking Australia make it to Indian shores. The day Indian audiences cast their net to patronise films of these countries too, Bollywood, in particular, and Indian film industries, in general, will be in for a torrid time.

Spielberg Fails To Get His Way At The Oscars

The battle was much awaited. Ground zero: conference room of Board of Governors of the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences; target: Netflix and other live streaming websites; attack led by: the one and only Steven Spielberg. The promised assault was mounted by Spielberg on the pre-determined April 23, and the verdict is out: Spielberg lost, Netflix survives to win another Oscar trophy in 2020, and for the Academy, it’s business as usual.

For all his revered standing in cinema, it was generally acknowledged that Spielberg had picked a wrong, possibly also unethical, cause. He had voiced his opposition to allowing films produced by live streaming sites to compete for the Oscars, and, probably, other major film awards too. He set up a rather specious and unacceptable argument that the primary market for films produced by Netflix was the small screen – TV set, laptop, smart phone – and hence its films should compete for Emmy Awards and not the Oscars. He termed these films as ‘TV films’ and was vehemently opposed to considering them as theatrical movies, and thereby sought to have them disqualified from the Oscars race. Last year, he particularly targeted Roma, Netflix’s Mexican film that walked away with three Oscars, including one for the Best Director, and carried out a sustained campaign to ensure that the next year, none of the films produced by streaming websites would be in contention at the Oscars.

He didn’t have much support from the Hollywood film industry, apparently. His old friends, compatriots in Spielberg’s five-decade journey in cinema, may have lent a shoulder or two but the younger generation of filmmakers weren’t impressed. Quite a few younger filmmakers openly and publicly disagreed with the old man of cinema, and the Academy has accepted their argument that films are films irrespective of the format favoured by its producers. As long as the film fulfils the mandatory condition of releasing in cinemas, it doesn’t matter whether bulk of its revenues come from the online market, the Academy added. Roma, for instance, had a short run in a limited number of cinemas to qualify for the Academy Awards, and then quickly made its debut online. Already in the run for the best film Oscars 2020 is Netflix’s The Irishman, which will have, predictably, a short run in cinemas before moving on to the streaming sites, and there’s nothing that Spielberg can do about it.

Spielberg’s friend and star of The Irishman, Robert De Niro, took a more pragmatic stand. He was quoted saying after the Academy’s decision to continue the status quo, and of rejection of Spielberg’s demand to ban films from streaming sites at the Oscars, “It’s not so simple and I agree, we have to have the theatre format, it’s so important. But I don’t know, things move on in ways that we can’t foresee.”

This is exactly what Spielberg needs to understand – things are moving so fast and in so many different ways that it would be rather naive to insist on sticking to the old ways. There’s no way of knowing what format of exhibition would be more popular in the years to come; unlikely, but it’s not improbable that cinemas, as we know them, may not exist 15-20 years from now, or all films would be VR, in which case, the experience of cinema would be individual, not collective as it is now. Spielberg needs to keep an open mind on the issue of film formats.